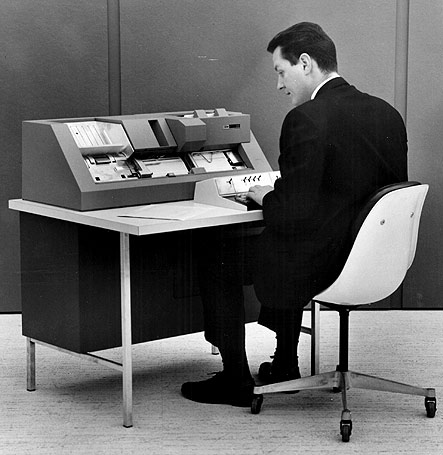

Just one of 21 cabinets making up the computer.

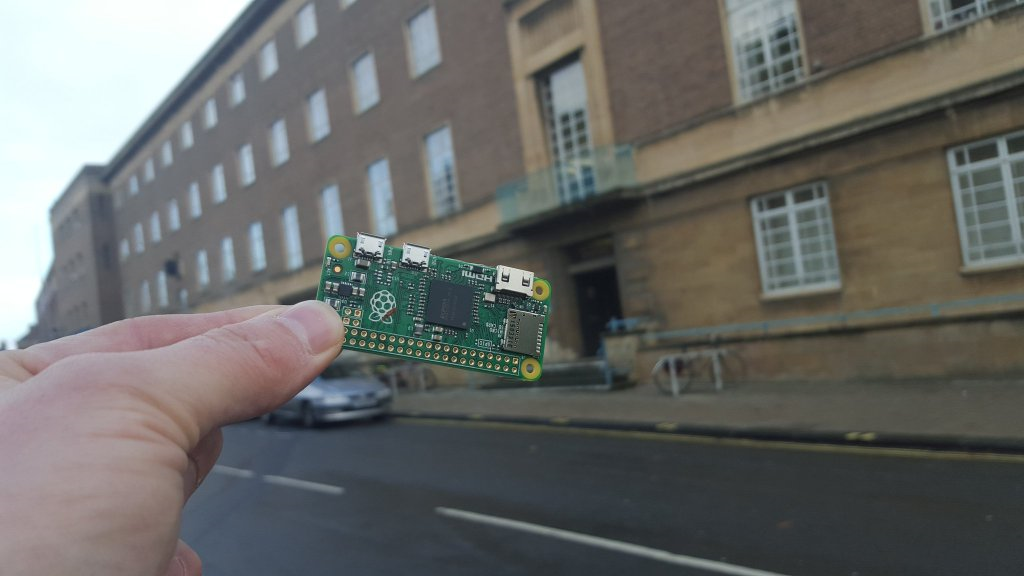

The first computer so cheap that they gave it away on the cover of a

magazine

The Elliot ran for about a decade, 24 hours a day.

How long do you think it would take the Raspberry Pi Zero to duplicate that amount of computing?

The Elliot ran for about a decade, 24 hours a day.

How long do you think it would take the Raspberry Pi Zero to duplicate that amount of computing?

The Raspberry Pi is about one million times faster...

The Raspberry Pi is not only one million times faster. It is also one millionth the price.

A factor of a million million.

A terabyte is a million million bytes: nowadays we talk in terms of very large numbers.

Want to guess how long a million million seconds is?

The Raspberry Pi is not only one million times faster. It is also one millionth the price.

A factor of a million million.

A terabyte is a million million bytes: nowadays we talk in terms of very large numbers.

Want to guess how long a million million seconds is?

30,000 years...

A really big number...

In fact a million million times improvement is about what you would expect from Moore's Law over 58 years.

Except: the Raspberry Pi is two million times smaller as well, so it is much better than even that.

In the 50's, computers were so expensive that nearly no one bought them, nearly everyone leased them.

To rent time on a computer then would cost you of the order of $1000 per hour: several times the annual salary of a programmer!

When you leased a computer in those days, you would get programmers for free to go with it.

Compared to the cost of a computer, a programmer was almost free.

In the 50's the computer's time was expensive. A

programmer would:

In the 50's the computer's time was expensive. A

programmer would:

Why? Because it was much cheaper to let 3 people check it, than to let the computer discover the errors.

The first programming languages were designed in the 50s.

They were designed with the economic relationship of computer and programmer in mind.

It was much cheaper to let the programmer spend lots of time producing a program than to let the computer do some of the work for you.

Programming languages were designed so that you tell the computer exactly what to do, in its terms, not what you want to achieve in yours.

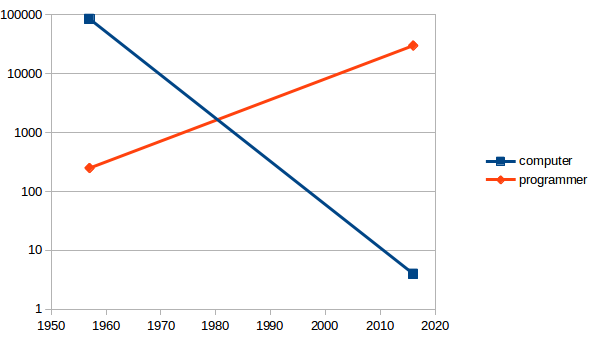

It happened slowly, almost unnoticed, but nowadays we have the exact opposite position:

Compared to the cost of a programmer, a computer is almost free.

I call this Moore's Switch.

Relative costs of computers and programmers, 1957-now

But, we are still programming in programming languages that are direct descendants of the languages designed in the 1950's!

We are still telling the computers what to do.

A new way of programming: declarative programming.

This describes what you want to achieve, but not how to achieve it.

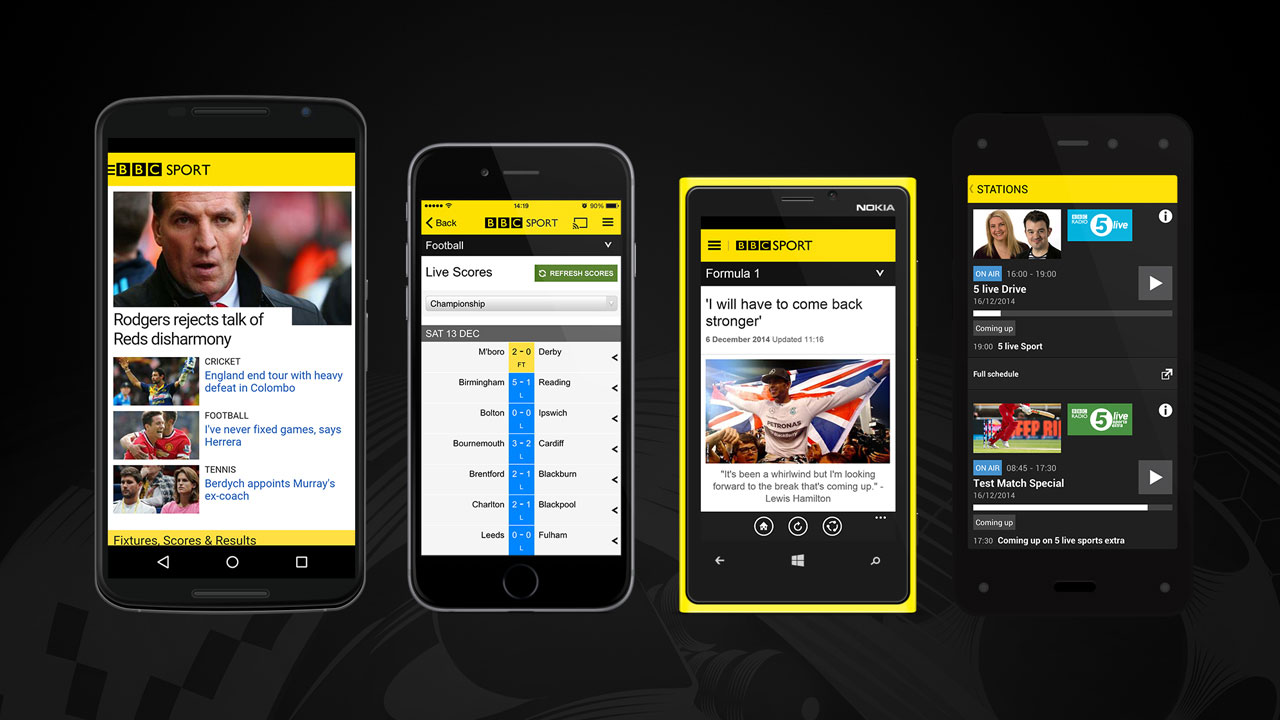

XForms is a declarative system that lets you define applications.

It is a W3C standard, and in worldwide use.

A certain company makes one-off BIG machines (walk in): user interface is very demanding — traditionally needed 5 years, 30 people.

With XForms this became: 1 year, 10 people.

Do the sums. Assume one person costs 100k a year. Then this has gone from a 15M cost to a 1M cost. They have saved 14 million! (And 4 years)

Manager: I want you to come back to me in 2 days with estimates of how long it will take your teams to make the application.

Manager: I want you to come back to me in 2 days with estimates of how long it will take your teams to make the application.

[Two days later]

Programmer: I'll need 30 days to work out how long it will take to program it.

Manager: I want you to come back to me in 2 days with estimates of how long it will take your teams to make the application.

[Two days later]

Programmer: I'll need 30 days to work out how long it will take to program it.

XFormser: I've already programmed it!

The British National Health Service started a project for a health records system.

The British National Health Service started a project for a health records system.

One person then created a system using XForms.

XForms 1.0 was designed for online Forms.

After some experience it was realised that the design had followed HTML too slavishly, and with some slight generalisation, it could be more useful.

So was born XForms 1.1, a Turing-complete declarative programming language.

Implementations from Belgium, France, Germany, NL, UK, USA.

XForms 2.0 is in preparation.

And I am here today to tell you about it.

"The term form refers to the work's style, techniques and media used, and how the elements of design are implemented.

Content, on the other hand, refers to a work's essence, or what is being depicted."

This is a nearly-perfect description of XForms.

XForms applications have two parts

XForms is all about state. (Which means it meshes well with REST - Representational State Transfer).

Initially the system is in a state of stasis.

When a value changes, by whatever means, the system updates related values to bring it back to stasis.

This is like spreadsheets, but much more general.

The result is: programming is much easier, since the system does all the administrative work for you.

I've got a position in the world as x and y coordinates, and I want to display the map tile of that location at a certain zoom.

My data:

x, y, zoom

Openstreetmap has a REST interface for getting such a thing:

http://openstreetmap.org/<zoom>/<x>/<y>.png

The coordinate system changes at each level of zoom.

As you zoom out, there are in each axis half as many tiles, so there are ¼ as many tiles. And the interface indexes tiles, not locations.

So to get a tile:

The data: x, y, zoom

scale = 226 - zoom

tilex = floor(x/scale)

tiley = floor(y/scale)

url = concat("http://tile.openstreetmap.org/", zoom, "/", tilex, "/", tiley, ".png")

That is really all that is needed (modulo syntax, which looks like this:)

<bind ref="tilex" calculate="floor(../x div ../scale)"/>

That's the form. Now the content:

<input ref="x" label="x"/> <input ref="y" label="y"/> <input ref="zoom" label="zoom"/> <output ref="url" mediatype="image/*"/>

and the tile will be updated each time any of the values change.

Separation of data from UI, similar to separation of style from content with CSS, with similar advantages.

Instances of data + properties.

<instance src="sale.xml"/> <bind ref="something" property="something"/>

Properties include:

As you saw above in the map example, whenever a value changes, the related values are automatically updated, in spread-sheet style.

<bind ref="address/state"

required="../country = 'USA'"

label="State"/>

This means that state is only required for the USA. The field

will always be visible.

<bind ref="address/state"

relevant="../country = 'USA'"

required="true()"

label="State"/>

This means that state will only be visible for the USA, but

once visible will be required.

Controls in the UI then bind to data nodes, inheriting their properties.

<input ref="address/state"/>

Similarly, the billing address is only relevant if it is different from the delivery address:

<bind ref="address[@type='Billing']"

relevant="../@different=true()"/>

Typically XForms works automatically.

You can hook into the processing model to respond in special ways.

Events announce changes in the state;

actions effect changes to the state.

E.g. xforms-ready announces that the system has initialised (and is at stasis). You could respond to this by recording today's date and time:

<action ev:event="xforms-ready"> <setvalue ref="today" value="now()"/> </action>

Other events announce when a value changes, or when it changes validity, relevance, etc.

Other useful actions include activating a button, and inserting and deleting elements and attributes from data.

In fact the only way to get a vanilla button to do anything is to listen for the activation event, and then respond with an action.

<trigger label="Restart">

<action ev:event="DOMActivate">

<setvalue ref="score" value="0"/>

</action>

</trigger>

The user-facing part is done with controls.

Controls are declarative too: they are designed to be device and modality independent;

Controls describe what they do, but not how they do it, nor how they look.

For instance, the select1 control selects a value from a list

of values. It can be implemented visually as a menu, or as radio buttons, and

it can be implemented in other modalities as necessary.

<select1 ref="colour"> <label>Colour:</label> <item><label>Red</label><value>red</value></item> <item><label>Yellow</label><value>yellow</value></item> <item><label>Green</label><value>lime</value></item> <item><label>Cyan</label><value>aqua</value></item> <item><label>Blue</label><value>blue</value></item> <item><label>Magenta</label><value>fuchsia</value></item> <item><label>Black</label><value>black</value></item> <item><label>White</label><value>white</value></item> </select1>

For instance these three are just different visual representations of this control:

Download XSLTForms, and unpack it in a directory.

Write your XForm using this template, filling in the correct directory:

<?xml-stylesheet href="directory/xsltforms.xsl" type="text/xsl"?>

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml"

xmlns:ev="http://www.w3.org/2001/xml-events">

<head>

<title></title>

<style type="text/css">

</style>

<model xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2002/xforms">

<instance>

<data xmlns="">

</data>

</instance>

</model>

</head>

<body>

<group xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2002/xforms">

</group>

</body>

</html>