Searching

Steven Pemberton, W3C/CWI, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Researcher at the Dutch national research centre CWI (first European Internet site)

Co-designed the programming language ABC, that was later used as the basis for Python

In the late 80's designed and built a browser, with extensible markup, stylesheets, vector graphics, client-side scripting, etc. Ran on Mac, Unix, Atari ST

Organised 2 workshops at the first Web conference in 1994

Co-author of HTML4, CSS, XHTML, XML Events, XForms, etc

Chair of W3C HTML and Forms working groups

Until recently Editor-in-Chief of ACM/interactions.

But has become a sort of Garden of Eden, with lots of Thou Shalt Nots in the form of guidelines

etc, etc, etc

And these communities have all come to the HTML working group to ask for new facilities.

In designing XHTML2, a number of design aims were kept in mind to help direct the design. These included:

As generic XML as possible: if a facility exists in XML, try to use that rather than duplicating it. This means that it already works to a large extent in existing browsers (main missing functionality XForms and XML Events).

Less presentation, more structure: use stylesheets for defining presentation.

More usability: within the constraints of XML, try to make the language easy to write, and make the resulting documents easy to use.

More accessibility: 'designing for our future selves' – the design should be as inclusive as possible.

Better internationalization.

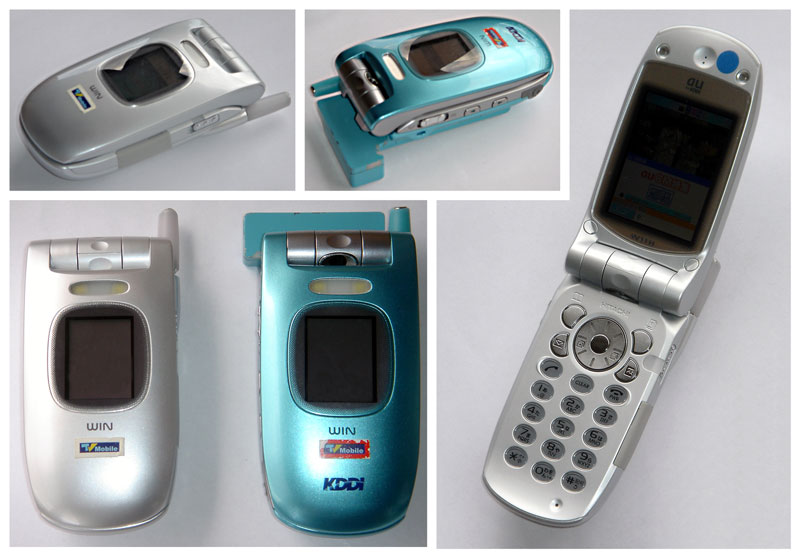

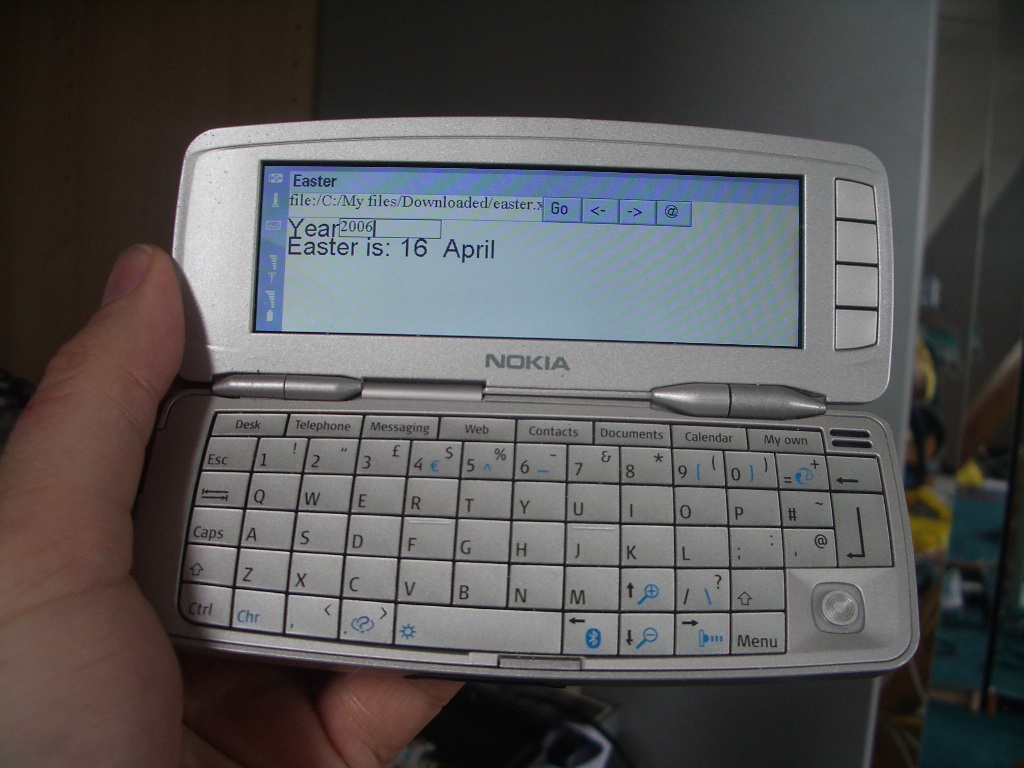

More device independence: new devices coming online, such as telephones, PDAs, tablets, televisions and so on mean that it is imperative to have a design that allows you to author once and render in different ways on different devices, rather than authoring new versions of the document for each type of device.

Better forms: after a decade of experience, we now know how to make forms a better experience.

Less scripting: achieving functionality through scripting is difficult for the author and restricts the type of user agent you can use to view the document. We have tried to identify current typical usage, and include those usages in markup.

Better semantics: integrate XHTML into the Semantic Web.

Keep old communities happy

Keep new communities happy

Earlier versions of HTML claimed to be backwards compatible with previous versions.

For instance, HTML4

<meta name="author" content="Steven Pemberton"> puts the content in an attribute and not in the content of the element for this reason.

In fact, the only version of HTML that is in any sense backwards compatible is XHTML1 (others all added new functionality like forms and tables).

XHTML2 takes advantage of CSS not to be element-wise backwards compatible, but architecturally backwards compatible.

For instance, as mentioned already, much of XHTML2 works already in existing browsers.

XHTML2 is recognisably a family member:

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2002/06/xhtml2/" xml:lang="en">

<head>

<title>Virtual Library</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Moved to <a href="http://example.org/">example.org</a>.</p>

</body>

</html>

This is not a tutorial, but I should draw attention to a couple of new features.

In certain places in HTML4/XHTML1 you can say that an element applies only to a specific media, like:

<style media="print" ...>...

This now applies across XHTML2, to any element.

<p media="screen">This text is only visible on a screen, not on the printed or projected version</p>

Metadata is becoming one of the most important new features of the web. The Semantic Web community has been working for years to integrate metadata properly with XHTML.

Metadata is sprinkled across HTML in lots of places:

etc etc.

XHTML2 creates a unified story about metadata, by relating it to RDF, however without confronting the HTML author with RDF.

RDF is the basis for the Semantic Web

It is a very simple mechanism for representing knowledge.

There are RDF databases and inference engines emerging that can represent the knowledge, and work out conclusions from it.

If a search engine or a browser can work out more about your document than just the text that is in it, searches and other interactions can become better.

For instance, if it can work out that in a page the text "the prime minister" refers to Tony Blair, then a search for Tony Blair could take you to that page, even if it doesn't mention him by name.

If the browser can work out that some text is an address, it can offer to add it to your address book, or find it on a map.

If a browser can work out that some text is for a conference, it could offer to add it to your calendar, or find flights and hotels.

There are several RDF serialisations, such as 'triples', and RDF/XML.

XHTML2 introduces a new representation for RDF assertions by leveraging the existing <meta> and <link> elements of HTML.

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-syntax-grammar">

<ex:editor>

<rdf:Description>

<ex:homePage rdf:resource="http://purl.org/net/dajobe/"/>

<ex:fullName>Dave Beckett</ex:fullName>

</rdf:Description>

</ex:editor>

<dc:title>RDF/XML Syntax Specification (Revised)</dc:title>

</rdf:Description>

This says that the document "http://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-syntax-grammar":

<meta about="http://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-syntax-grammar">

<meta property="ex:editor">

<meta property="ex:fullName">Dave Beckett</meta>

<link rel="ex:homePage" href="http://purl.org/net/dajobe/" />

</meta>

<meta property="dc:title">RDF/XML Syntax Specification (Revised)</meta>

</meta>

'about' gives the subject (defaults to the current document)

'property' gives the predicate for a string or XML fragment; the object is in the element content (or the 'content' attribute).

'rel' gives the predicate for a URL: the object is in the href.

The attributes on <meta> and <link> can be used on any element. For instance:

<body>

<h property="title">My Life and Times</h>

...

is a way of saying that "My Life and Times" is both the <title> of this document, as the top-level heading.

You could do the following in HTML already, but now we can extract it as RDF as well:

This work is licensed under the <a rel="dc:rights"

href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/">

Creative Commons Attribution License</a>.

There is a standard filter called GRDDL for extracting the RDF from an XHTML2 document.

You can explain it using HTML concepts.

If you don't care, you can just ignore it.

It doesn't require you to learn how to use RDF to be able to benefit from it.

The RDF community get their triples without RDF being imposed on the HTML community.

This approach solves a lot of outstanding problems.

For instance, the Internationalisation community needed a way of adding

markup to a title attribute.

Now we can just say that

<p id="p123" title="whatever">

is equivalent to:

<p id="p123"> <meta about="#p123" property="title">whatever</meta>

And it solves the problem of everyone asking for new elements in XHTML: an element for <navigation>, an element for <note>s (in inline and block versions), an element for lengths, and numbers, and ...

But first a diversion...

The accessibility community needed a way to specify what a particular element was for.

Some examples: that a certain <div> was just a navbar, that another <div> was the main content, etc. So we introduced the 'role' attribute for this. You can now say:

<div role="navigation">...</div> ... <div role="main">...</div>

but once we had that mechanism, it allowed us to add any semantics we wanted, layering it on top of the structure. For example:

<p role="note">...

but also

<span role="note">...

<table role="note">...

role is in a way like class but with meaningful

(semantic) values.

In fact, anyone can add their own role values, so that whole communities can agree on new semantics to overlay on to the content.

Apparently the mobile and device-independent communities (as well as accessibility) are very excited about the possibilities of using role.

In fact, you don't really need RSS anymore:

<h role="rss:title">... <p role="rss:description">...

To go with the role attribute, there is a new way of doing accesskey (which used to be spread through the document). Now in the head you can say things like:

<access targetrole="main" key="M"/>

An advantage of this is that you can have different access keys for different media.

(There is also a targetid for individual elements.)

Events in HTML are very restrictive:

onflash if an event called

flash were introduced.So we invented a new markup for events.

<input type="submit" onclick="validate(); return true;">

is now

<input type="submit">

<handler ev:event="DOMActivate" type="text/javascript">

validate();

</handler>

</input>

We renamed <script> to <handler> because it is sufficiently

different to the HTML <script> to be confusing. In particular

document.write no longer works in XML.

This approach now allows you to specify handlers for different scripting languages:

<input type="submit">

<handler ev:event="DOMActivate" type="text/javascript">

...

</handler>

<handler ev:event="DOMActivate" type="text/vbs">

...

</handler>

</input>

and/or different events:

<input type="submit">

<handler ev:event="DOMActivate" type="text/javascript">

...

</handler>

<handler ev:event="DOMFocusIn" type="text/javascript">

...

</handler>

</input>

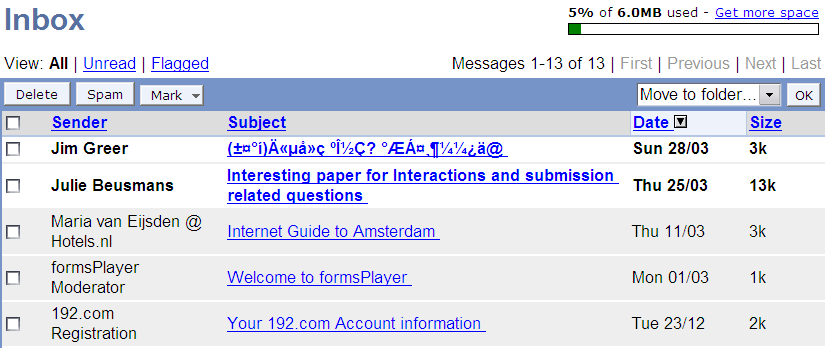

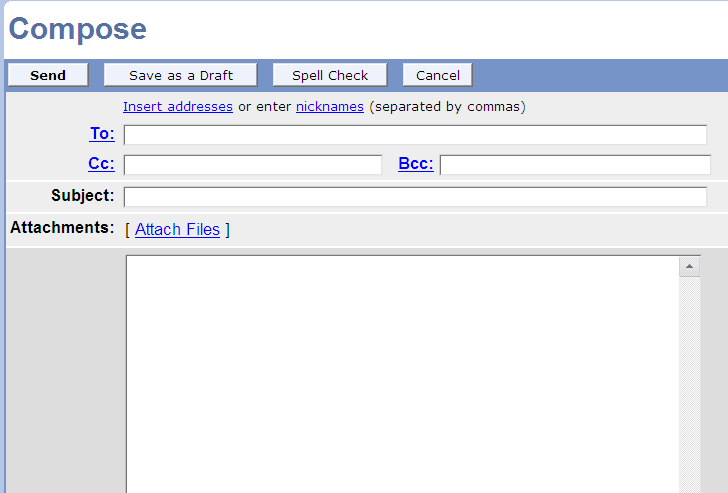

After a decade of experience with HTML Forms, we now know more about what we need and how to achieve it.

Soundbite: "Javascript accounts for 90% of our headaches in complex forms, and is extremely brittle and unmaintainable."

XForms has been designed based on an analysis of HTML Forms, what they can do, and what they can't.

There are two parts to the essence of XForms. The first is to separate

what is being returned from how the values are filled in.

The second part is that the form controls, rather than expressing how they should look (radio buttons, menu, etc), express their intent (this control selects one value from a list).

You then use styling to say how they should be represented, possibly with different styling for different devices (as a menu on a small screen, as radio buttons on a large screen).

XForms gives many advantages over classic HTML Forms:

XForms has been designed to allow much to be checked by the browser, such as

This reduces the need for round trips to the server or for extensive script-based solutions, and improves the user experience by giving immediate feedback on what is being filled in.

Because XForms uses declarative markup to declare properties of values, and to build relationships between values, it is much easier for the author to create complicated, adaptive forms, and doesn't rely on scripting.

An HTML Form converted to XForms looks pretty much the same, but when you start to build forms that HTML wasn't designed for, XForms becomes much simpler.

XForms is properly integrated into XML: it is in XML, the data it collects in the form is XML, it can load external XML documents as initial data, and can submit the results as XML.

By including the user in the XML pipeline, it at last means you can have end-to-end XML, right up to the user's desktop.

However, it still supports 'legacy' servers.

XForms is also a part of XHTML2.

Rather than reinventing the wheel, XForms uses a number of existing XML technologies, such as

This has a dual benefit:

Data can be pre-loaded into a form from external sources.

Existing Schemas can be used.

It integrates with SOAP and XML RPC.

Doesn't require new server infrastructure.

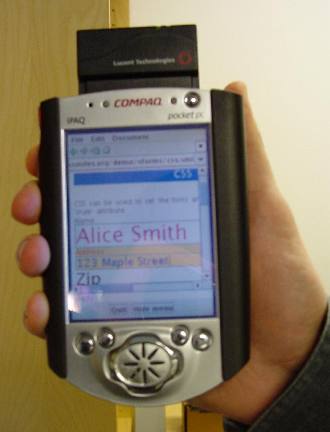

Thanks to the intent-based controls, the same form can be delivered without change to a traditional browser, a PDA, a mobile phone, a voice browser, and even some more exotic emerging clients such as an Instant Messenger.

This greatly eases providing forms to a wide audience, since forms only need to be authored once.

Thanks to using XML, there are no problems with loading and submitting non-Western data.

XForms has been designed so that it will work equally well with accessible technologies (for instance for blind users) and with traditional visual browsers.

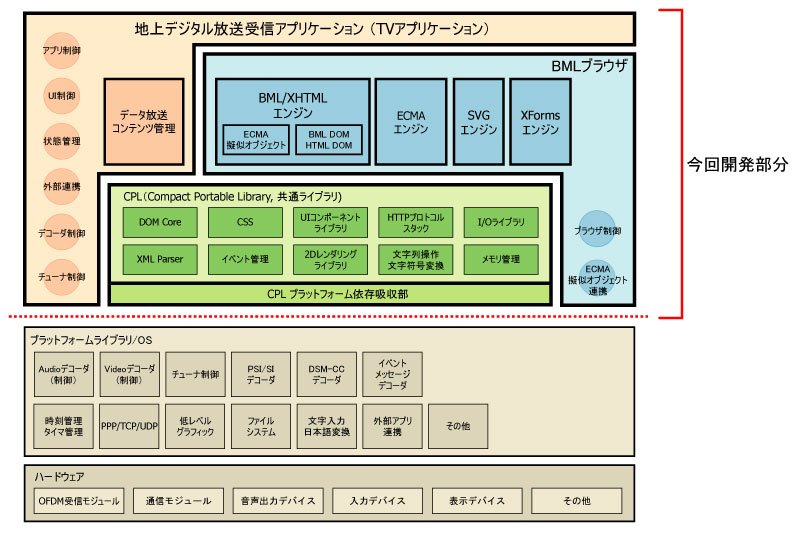

XMLDOMCSSJavascriptXHTMLXPathXForms

=Regular XHTML Browser

Time to build all of above: 3 programmers, 4 months

Total footprint (on IPAQ implementation): 400K (above Java VM)

In fact this is quite evolutionary: XForms uses existing W3C components. It is only the XForms processing model that describes when to calculate values that is really new.

Open standard

Wide industry support

Widely implemented

No vendor lock-in!

(If you think this is a good idea, join W3C!)

At release XForms had more implementations announced than any other W3C spec had ever had at that stage

Different types of implementation:

Many big players doing implementations, e.g.

As you would expect with a new technology, first adopters are within companies and vertical industries that have control over the software environment used.

That list is there just to give a taste, but amongst others not mentioned there are at least 3 fortune 500 companies not listed above who don't want it to be public knowledge so that their competitors don't get wind of it.

As more industries adopt XForms, the expectation is that it will then spread out into horizontal use.

XSmiles now running under J2ME PP

Again, this is not a tutorial

ref attribute on controls can be any XPath

expression<title> element in an

XHTML document

<input ref="/h:html/h:head/h:title">...

(i.e. the title element within the head

element within the html element, all in the XHTML

namespace)

class attribute on the body element:

<input ref="/h:html/h:body/@class">...

Suppose a shop has very unpredictable opening hours (perhaps it depends on the weather), and they want to have a Web page that people can go to to see if it is open. Suppose the page in question has a single paragraph in the body:

<p>The shop is <strong>closed</strong> today.</p>

Well, rather than teaching the shop staff how to write HTML to update this, we can make a simple form to edit the page instead:

<model>

<instance

src="http://www.example.com/shop.xhtml"/>

<submission

action="http://www.example.com/shop.xhtml"

method="put" id="change"/>

</model>

...

<select1 ref="/h:html/h:body/h:p/h:strong">

<label>The shop is now:</label>

<item><label>Open</label><value>open</value></item>

<item><label>Closed</label><value>closed</value></item>

</select1>

<submit submission="change"><label>OK</label></submit>

method="post"

method="put":<submission

action="file:results.xml"

method="put"/>

which saves your results to the local filestore by using the

file: scheme.

replace on the submission element.replace="instance" replaces only the instancereplace="none" leaves the form document as-is without

replacing it.XForms has everything needed for an application:

People are already using XForms for some pretty exciting applications. xport.net who produce FormsPlayer are doing the most interesting stuff, by using SVG as the stylesheet language. They have produced examples such as a world clock, a contacts database, and even Google Maps in XForms!

The interesting thing about this last example is that it is 25K of XForms, compared with 200K+ of javascript...

This is largely thanks to the declarative programming model of XForms, that means that you don't have to deal with lots of the fiddly administrative details.

Bear in mind that empirical evidence suggests that a program that is an order of magnitude larger takes 34 times as much effort; or put the other way, a program that is an order of magnitude smaller costs 3% of the effort...

XForms is achieving critical mass much faster than we had anticipated. Companies large and small, consortia, even governments and government agencies are beating a path to our door.

Apart from offering a far more managable base for forms on the web, we believe that XForms is an excellent basis for future web applications, because it offers a model that gives you:

XHTML2 has been designed on the basis of requirements from a large number of different communities.

It has been designed to be as recognisably XHTML as possible within the constraints of the new requirements.

It is going to last call shortly: we welcome your comments!

Steven Pemberton: www.cwi.nl/~steven